Here’s a quiz: I am holding a paint brush, I am dipping it in paint, I am applying the paint to the surface so as to manifest a two dimensional picture of an image that is held as an ideal in my imagination. What am I doing?

Answer: painting, right?

Wrong. It’s writing. Or at least it is according to some people, if the object you are working on is a holy icon.

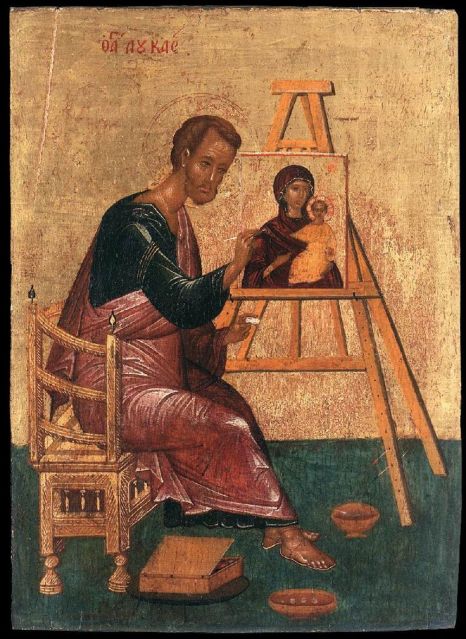

So, for example, those who think this would say that St Luke not only wrote inspired scripture, he also wrote an icon of Our Lady and Our Lord!

But is this right? Is painting really an inherently distinct and inferior activity to writing as an insistence on the use of the word write would seem to suggest? Also, why pick out a verb that relates to one particular aspect of Christ every single time, ie the Word? We say also that Christ is the image of the invisible God so why not make this aspect govern our verb use when creating holy images? If Christ is an image, then it seems that references to the ‘painting’ of an image seem reasonable. This after all is part of the justification for creating images worthy of veneration, according to the Seventh Ecumenical Council. And if we really do have to only think of Christ as the Word, then (reductio ad absurdum) why not be consistent and rather than talking of Our Lady giving birth to Our Lord, why not say she ‘wrote’ the Word made flesh?

Furthermore, why not use the principle of hierarchial vocabulary when we are talking of writing as…well writing – stringing words together to make sentences and paragraphs? We might say that the writer St Luke wrote his gospel, but hack David Clayton only hacked this blog piece, for example.

To my knowledge it is only in the English language and only since the 20th century that people have referred to the writing of icons in this particular way. It is true that in Greek and, I discovered recently, Russian that the verb, to paint a picture, is the same word as ‘to write’. However the same word is used for the painting of all pictures – not just icons but landscapes, portraits and so on also. The verb ‘to paint’ which does exist in Russian is used for a lesser form of painting – the painting of houses and fences and so on.

This doesn’t mean that those of us who speak English can’t decide to use the word ‘write’ for an icon if we want to. Perhaps it would be valuable to distinguish the creation of holy icons not only from the painting of the walls of a room, but also other lesser forms of art. However, as Catholics we do not necessarily acknowledge that the iconographic style is inherently superior to other all other styles of sacred art. If we follow the ideas of Benedict XVI then, I suggest, we woule refer to gothic and baroque art as works that are ‘written’ too. So Blessed Fra Angelico wrote the Annunciation:

Either that or, to be consistent, extend the use of the word write beyond just icons; or stop using it for paintings altogether and be happy with saying that just as Fra Anglico painted, so did St Luke.

Also, contrary to what some Catholic believe, it is not the case that all icon painters or Eastern Christians use the word write for what they do. My own teacher, who is Orthodox, always used to say that he thought that the use of the word ‘write’ was ‘a bit precious’. This did not mean that he didn’t think that the painting of icons wasn’t a noble activity.

In 1975, Tom Wolfe – the guy who wrote The Bonfire of the Vanities – wrote a brilliant essay about the absurdities of modern art called The Painted Word. He pointed to the fact that the whole art scene is a gallery-art driven business in which the sellers manipulate the market by appealing to the vanity of buyers and intellectuals.. They flatter them by making them think they must be very clever to understand the nonesensical art theory that was used to justify the art they were looking at and which mystifies all clear thinking people who have no pretences to being an aesthete.

The title of the book, the The Painted Word, arises from the fact that the flattery of the clients was so important to sales that the ideas behind the theory was considered more important than physical manifestations of them, the art itself – to be an modern art officianado is be clever because you understand it, not necessarily because you like it. The artists, faithfully following the theorists in order to sell their work at inflated prices, gradually moved into greater and great abstraction, trying to show the pure non-physical idea through a physical medium. They struggled to do so because the ideas weren’t really coherent. In the end the connection between art and ethos was so obscure that they had to write a long explanation next to the exhibit in order for anyone to understand what was going on. The natural extention of this, Wolfe points out, is to abandon conventional art altogether and just paint the words that represent the idea. This is indeed what happened to modern art. It became an high stakes game of painted word association.

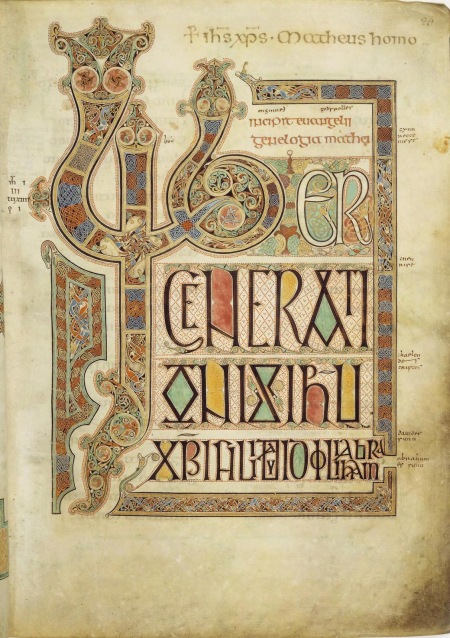

Wofe’s description of the inadequacies of modern art highlight by contrast the richness of traditional sacred art. Because the ethos of Christian sacred art is rooted in truth we can manifest those ideas well. So we not only have writers who write the Word in words, we have painters who paint the Word made flesh as an image, and can even do so in such a way, so the Catechism tells us, that they are able to communicate things that words alone cannot. Furthermore, the Christian tradition also has those who paint words beautifully when they write the Word – they are called calligraphers! The creator of the Lisfarne gospel, shown below, was simultaneously a painter of words, and writer of the Word I suggest.

Where do I stand on this issue? Personally, I am less worried about what you call the activity of painting/writing icons than I am about how well it is done. To insist on the use of the word ‘write’ in a way that is not common practice in the English language feels to me like a bit of unnecessary faux-theological political correctness. So I don’t mind if others do it, but I’m not moved to do it myself. As far as I am concerened, the word ‘paint’ describes more than adequately what the sacred artist does and we don’t need to play word games in order to raise the status of the artist’s vocation. Ultimately, it is artists themselves who will do that by raising the quality of the work that they produce.

Postscript: those who wish to know a range of views held by Orthodox Christians on this matter might be interested in these three thoughtful articles in the Orthodox Arts Journal, here: Is Write Wrong?, here: A Symptom of Modern Blindness; and here: From Logos to Graphos, Lost in Translation. (I love the headlines of the articles by the way. Congrats to the OAJ sub-editor who composed them – they’re so good I thought of stealing them for myself!)

Hello and thanks for the article,

As an icon writer, I am partial to the word ‘writer’ as opposed to ‘painter’ in regards to icons because I am not the artist, the Holy Spirit is.

An icon is written through the hands of a person as a result of prayer and the guidance of the Holy Spirit. Iconographers cannot take credit for God’s work, thus they ideally remain anonymous and do not sign the piece but refer to themselves as writers because the Holy Spirit dictates the work.

There is a bit of ‘self’ when an iconographer mentions themselves as the creator, because in reality, that is contradictory to the creation of the icon because their purpose is to point to God and not to deter from that in any way. God is the point of icons, so words that are proper forms of English or how things should be ideally phrased don’t really matter because in reality they are not even truly fitting.

On the back on an icon image, perhaps, the person will inscribe, ‘Written through the hands of…..’ and then their initials. Why we feel the need to do this seems to be mostly human vanity.

The creation of an icon is a work of service and humility. The image in the icon is made present for those who venerate it. That is not something an artist does, but that the Holy Spirit does. Icons are not a reflection of self, but of the Holy Spirit and the word ‘painting’ is a reflection of self, whereas ‘writing’ portrays the intermediary aspect of the gift that the iconographer has received through the guidance of the Holy Spirit, Who inspires and enlivens it.

Thanks!

LikeLike

Hello Nancy

I take your point. The question is why does the word ‘write’ indicate more of an involvment of the Holy Spirit that the word ‘paint’? And also, doesn’t the Holy Spirit inspire all good art, not just icons or sacred art? Given this, I don’t see a reason why ‘write’ might be considered a higher word or more associated with the Holy Spirit than the word ‘paint’. Inspired painting is just as noble as inspired writing, isn’t it? Also, I am not aware of any other language that differentiates between the painting of icons and other sorts of painting in this way. So I was told for example, that Russian, Greek and Ukrainian, do not, all countries whose culture has a longstanding connection with icons and which would happily accept your description that the creation of good icons is an inspired process. These languages use the same word for painting a landscape as they do painting an icon. It seems it is only amongst some English speaking icon painters that this distinction has developed English language, and even then, only since the middle of the 20th century.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your reasons make sense to me, David. The term, at least in English, has from the first, struck my ear as contrived.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent article David , I have always told my students that in my opinion to say we ‘write ‘ icons is a bit of a linguistic affectation.

Peter Murphy

LikeLike