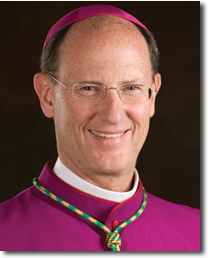

I would encourage all to visit the website of the Southern Nebraska Register. This is the newspaper for the Diocese of Lincoln, Nebraska. Bishop James Conley, the Bishop of Lincoln, contributes regularly and his writings are worthy of study. He has a strong interest in the connection between the practice of the Faith, with the worship of God in the sacred liturgy at its heart, and its impact on every aspect of the culture. This is further indicated by the beautiful new church at the Newman Center at the University of Nebraska and the Great Books programs that he has intiated at the Newman Institute there and which focus on the how the beauty of a Christian culture draws us to the Faith.

This week Bishop Conley writes:

More than 70 years ago, the English satirist Aldous Huxley wrote that modernity is the “age of noise.” He was writing about the radio, whose noise, he said “penetrates the mind, filling it with a babel of distractions – news items, mutually irrelevant bits of information, blasts of corybantic or sentimental music, continually repeated doses of drama that bring no catharsis.”

More than 70 years ago, the English satirist Aldous Huxley wrote that modernity is the “age of noise.” He was writing about the radio, whose noise, he said “penetrates the mind, filling it with a babel of distractions – news items, mutually irrelevant bits of information, blasts of corybantic or sentimental music, continually repeated doses of drama that bring no catharsis.”

If Huxley had lived into the 21st century, he would have seen the age of noise redoubled and amplified beyond the radio, first to our televisions, and then to our tablets and mobile devices, machines which bring distraction, and “doses of drama,” with us wherever we go. We are, today, awash in information, assaulted, often, with tweets and pundits analyzing the latest crisis in Washington, or difficulty in the Church, or serious social, political, or environmental issue. It can become, for many people, overwhelming.

To be sure, we have a responsibility as faithful Catholics to be aware of the world and its challenges, and to be engaged in the cultural and political affairs of our communities. We cannot shirk or opt out from that responsibility. But we are living at a moment of constant urgencies and crises, the “tyranny of the immediate,” where reactions to the latest news unfold at a breakneck pace, often before much thought, reflection or consideration. We are living at a moment where argument precedes analysis, and outrage, or feigned outrage, has become an ordinary kind of virtue signaling—a way of conveying the “right” responses to social issues in order to boost our social standing.

The 2016 presidential election was a two-year slog of platitudinous and superficial argument, and now that the election is over, that argument seems interminable. No person can sustain the kind of noise—polemical, shrill, and reactive—which has become a substitute for conversation in contemporary culture. Nor should any person try. The “age of noise” diminishes virtue, and charity, and imagination, replacing them with anxiety, and worry, and exhaustion.

The Lord didn’t make us for this kind of noise. He made us for conversation, for exchange and communion. And our political community depends upon real deliberation: serious debate and activism over serious subjects. But the Lord also made us for silence. For contemplation. For quietude. And without these things anchoring our lives, and our hearts, the age of noise transforms us, fostering in our hearts reactive and uncharitable intemperance that characterizes the media and social media spaces which shape our culture.

The age of noise is grinding away at our souls.

In the second century, just 100 years after Christ’s Ascension, an anonymous Christian disciple wrote a letter to a man named Diognetus, telling him something about the lives and practices of early Christians. “There is something extraordinary about their lives,” he wrote. “They live in their own countries as though they were only passing through…. They pass their days upon earth, but they are citizens of heaven.”

When our friends and neighbors look to us, as disciples of Jesus, they should see that there is something extraordinary about our lives: that although we live fully in our nation, we are, first, citizens of heaven. This means that we must live differently, in the age of noise. We must speak, and act, and think differently. In the words of St. Paul, we must “not be conformed to this world,” to the age of noise, “but be transformed by the renewal of our minds.” We must be, in the best sense of the word, “counter-cultural.”

To be citizens of heaven, we must be detached from the noise of this world. We must participate fully in cultural, and political, and public life, but we must entrust the outcomes of our participation to the Lord. We must detach ourselves from the news cycles, and social media arguments, and television pundits, which inflame our anger, or provoke our anxiety, or which shift our focus from the eternal to the fleeting and temporal.

My good friend Chris Stefanick, a wise speaker and author, wrote last week that we should “read less news,” and “read more Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.” He’s right. We won’t be happier, or wiser, or more peaceful because we consume more of the “age of noise” than we need. Of course, we should be engaged in current affairs. But we’ll be truly happy, through Jesus Christ, when we spend far more time reading Scripture, and spending time before the Lord in adoration of the Blessed Sacrament.

We’ll be free from the anxiety and worry of the “age of noise” when times of prayer, and silence, are regular facets of our day. We’ll be detached from false crises and urgency of the culture of outrage when we do our small part, and then entrust the affairs of this world to the Lord. We’ll also be, when we quiet the “age of noise” in our hearts, the leaders of wisdom and virtue which our culture desperately needs, right now.

Saint Teresa of Avila, the great Carmelite mystic, wrote a small poem which should guide us in the “age of noise” —

Let nothing disturb you,

Let nothing frighten you,

All things are passing away:

God never changes.

Patience obtains all things

Whoever has God lacks nothing;

God alone suffices.

The noise of our culture is designed to disturb and frighten us, and to distract from the unchanging and ever-loving God. But in silent prayer and contemplation before the Blessed Sacrament, we can turn down the noise, and the Lord himself can calm our hearts and renew our minds. To live extraordinary lives, as citizens of heaven before all else, it’s time that we turn down the “age of noise.”

Afterword by David Clayton: I chose to add this particular painting of St Theresa to Bishop Conley’s article because, unlike other more famous images this shows her in what we are more likely to think of as a contemplative state – one that suggests peace.

At first sight this contrasts with the more well known, but nevertheless strikingly beautiful sculpture of her by Bernini, to take one example, and which indicates the power of God by portraying her in ecstacy during a vision. However, it seems to me that these are not contradictory. Rather, both are attempts to portray a saint who experiences peace, albeit a special sort of peace. This peace is a supernatural reality, a peace that is more powerful than the noise of the modern world, as Bishop Conley points out. I always have a tendency to think of peace as the absence of noise, rather than the presence of something positive that engenders calm; but it strikes me that the juxtoposition of these two images points us, through their portrayal of different facets of the same precious jewel, to the awesome power of God that is simultaneously dynamic and peaceful. This is after all a peace that ‘passeth understanding’. Furthermore in Bernini’s statue St Theresa is experiencing, according to my understanding of the meaning of the word what the goal of contemplation is – to be receptive to a gift from God, should he choose to give it to us, in which he makes Himself know to us supernaturally. In that sense one might even argue that it is even more intensly contemplative than Gerard’s painting.

I cannot say for certain that it was Bernini’s intention, and I may well be seeing what I am trying to look for, but I see in the face of St Theresa a calmness at the center of the vigorous motion that is suggest by the rest of the sculpture. Regardless, if I was sculpting her…and had the capabilities…that is how I would sculpt it!

David,

Just to clarify the statue by Bernini depicts the transverberation of Theresa of Avila’s soul. More than ecstasy, the angel pierces her soul with an arrow. She writes about this in her autobiography. So more than “just”ecstasy, this could compare with perhaps, St.Francis receiving the stigmata.

LikeLike

Thank you Nancy. Yes you are right. I think that the underlying point is still the same, that there is a peace that transcends even the apparently negative aspects of this gift from God, would you agree? It is a seemingly paradoxical thing, but St John of the Cross describes something similar it seems to me. The Dark Night is not a bad thing, and is not a state of unhappiness. Whatever bodily pleasures are withdrawn and the distress that this might cause, is transcended by the consolation of an awareness of the presence of God.

LikeLike