It is no accident that Easter happens in the spring, during that time of year when the earth is reawenaking (at least in the northern hemisphere). The days are growing longer, trees are nearly luminous with green budding leaves, and blossoms are bursting vibrant pinks, purples, reds, and white. Trumpeting Easter lilies announce the Resurrection best with their bright fragrance and simple purity.

We take for granted that Christ is the Light of the World. The role of darkness and light has a long and illustrious history in understanding the Christian moral order.

Christians certainly aren’t the only ones to recognize the value of light. In Plato’s cave allegory in The Republic, most souls are chained in position in the cave, looking at shadows cast on a cave wall by fire, believing the shadows to be the really real. The wise souls, on the other hand, are able to ascend up into the light of day outside the cave and see things as they really are. What Plato and Socrates did not know, however, was that the light of the world wasn’t an element of nature, but an actual person, both man and God.

Light became a particularly important theme early in the Christian story; Christ and sacred scripture gave the notion of light a new blessing. A deeper understanding of the luminous concept started at the end of the Dark Ages and the dawn of the Medieval Period. St. Bernard of Clairveaux, explaining the role of light in the moral and intellectual life, wrote: “He who is by his former life and conscience was doomed as a true son of perdition to the eternal flames, draws new life and hope beyond all expectation. [He is] rescued from a most deep and dark pit of horrible ignorance, and plunged into a pleasant region bright with eternal light.”

In the realm of scholastic philosophy, Robert Grosseteste, building upon St. Augustine’s use of light, would look at it with new eyes – both theological and scientific. “No created truth,” the English bishop explained, “can be perceived except in the light of the supreme Truth, God.” Even today, Grosseteste is given credit for as a first spark for the scientific method, having experimented extensively with the in the physical form, while grappling with it intellectually.

Other thinkers would develop their own theories of divine illumination – a distinctively medieval notion that considers an enlightening of the mind directly or indirectly by God (depending upon the theory). This theory, however, while important in understanding eternal and philosophical truths, was also tightly connected to the idea of virtue and growing in sanctity. Without out The Light, there is only moral darkness.

It is no accident, then, that the promoters of these theories have similar titles: Saint Bonaventure, Saint Thomas Aquinas, Saint Anselm of Canterbury, Saint Albert the Great, and Blessed Duns Scotus. All were scholars and holy, holy men.

Beyond the Schoolmen, there was also Saint Hildegard of Bingen, who, though not at all well educated, understood a type of illumination theory given to her directly by God. Hildegard, made a saint and doctor of the Church by Pope Benedict XVI, wrote many divinely inspired books about the Trinity, with the recurrent theme of light and fire. “Heaven was opened and a fiery light of exceeding brilliance came and permeated my whole brain and inflamed my whole heart and my whole breast.” Light, particularly as a concept to understand God’s nature and power, is explained in very detailed and compelling terms.

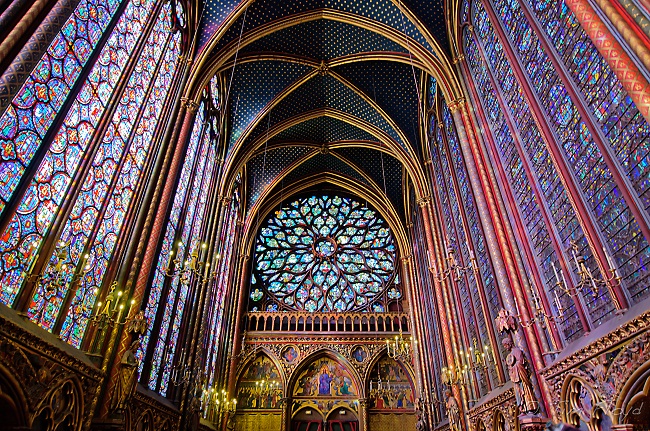

This love of light bled out also into architecture. The New Style (as it was known then), or Gothic architecture pulled out all the stops to move away the dark shadows, heavy columns, and narrow windows of the Romanesque period. In their absence, soaring ceilings and expansive windows let in more light than was ever-dreamed possible. Even the flying buttresses were frozen in place so more heavy stones could be removed, with glass to go in their stead. Abbot Suger, who commissioned the Church of St. Denis to be built, wrote: “If a church’s interior should be an image of heaven for the faithful, then entering the Church of Saint Denis meant entering a heaven of light and color and a radiant, eternal divine proportion.”

Even a child knows that when there is no light, there is only darkness. Ironically, after this era of so much light, the philosophies that followed it were given the name “enlightened.” The Enlightenment philosophers rejected all that they considered dark, backward, and superstitious, which ultimately meant extinguishing the Eternal Light.

Our contemporary culture lives in the shadow of the enlightenment, placing much more trust in science than the God who gave us science. The fruit of it, on the one hand is the ability to flip on a switch and light up even the darkest night (gratefully). But what have we to show for it in our souls? What remains looks a lot more like the poor souls stuck in Plato’s cave – where we sit and look at images on the wall, believing them to be real (the irony that I’m writing this in a dark room looking at a glowing screen is not lost on me). Meanwhile the Eternal Light, the Divine Truth, and the brilliance of the really real wait quietly for our restless souls to ascend to up into their radiance again.

Carrie Gress is on the faculty of Pontifex University, her unique course, which will be offered as part of the Masters in Sacred Arts starting this summer, is A Survey of the Philosophy of Beauty, Truth and Goodness from the Ancient Greeks to the Present Day.

Her latest book, The Marian Option, God’s Solution to a Civilization in Crisis is published by Gracewing.

Pictures: the interior and stained glass of the upper church; and the painted lower church of the gothic Sainte Chapelle in Paris.