More on the assumption of Mary

David Clayton’s recent post on the assumption of Mary was very timely for me, as I am currently preparing the lesson about the union of body and soul for the upcoming Pontifex course on The Philosophy of Nature and Man!

As David mentioned, there is some ambiguity about the vital status of the Blessed Mother at the time of his assumption. Did she really die, or did she “fall asleep” in an in-between state of dormition whereby her body was preserved?

The question of the preservation of the body is of great philosophical interest, although I must admit that philosophy alone cannot settle the question of Mary’s assumption, but only identify the relevant metaphysical aspects of the mystery.

Philosophers have long postulated the existence of the soul as the principle of life: that by which a body is made a living body. More controversial, however, is the position taken by Aristotle and St. Thomas Aquinas–and not necessarily shared by all Christian philosophers–that the soul is also the form of the body, meaning the principle “by which a body is a body.” Some philosophers preferred instead to invoke a principle of “corporeity,” independent from the soul.

For St. Thomas, it is essential to have the soul fulfill both roles of “actualizing matter” into a body and of animating that body with life. Otherwise, we wouldn’t be the kinds of unified beings that we experience ourselves to be. On the other hand, his opponents would argue that the body seems to remain “one thing” after natural death, which suggests a separate substantial form for the human body. (I personally think Thomas was correct, and I have an explanation for the question of the status of the “dead body,” but if you want to know what I think, you’ll have to join us when the course is up!)

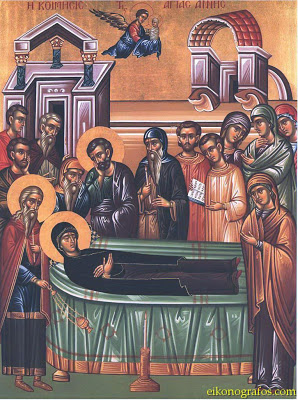

I was very interested in the icons and sacred images of the assumption that David showed in his post. David is right in drawing attention to the tomb. If there was a tomb, then certainly Mary must have appeared sufficiently dead to those who were with her at the end that they proceeded with a burial. It’s unlikely they were mistaken. But, if that’s the case, wouldn’t her soul have been separated from the body at that point? And, if so, was a lifeless body assumed into heaven alongside—but separately from—the soul?

It seems that the various artists have interpreted the event in various ways. In some of the paintings, the body being assumed appears very much alive, but not in all of them. In two paintings, Mary is looking upward to Heaven, with a trance-like daze. In the two icons, on the other hand, the eyes are closed and the posture is still and lifeless, while the soul of Mary is represented as a white clad figure in the arms of Jesus. I guess the jury of artists is still out as to what really happened!

If, as David notes, Pope Pius XII left the question of her death open, Pope St. John Paul II, on the other hand, stated emphatically in favor of Mary’s natural death. In a general audience in 1997, the pope said that “to share in Christ’s Resurrection, Mary had first to share in his death.” He also mentioned St. Francis de Sales’ wonderful insight that “Mary’s death was due to a transport of love,” and concluded that “for Mary, the passage from this life to the next was the full development of grace in glory, so that no death can ever be so fittingly described as a ‘dormition’ as hers.”

Here is an icon of the Feast of the Dormition of St Anna, the Mother of Our Lady, which is celebrated on July 25th in the Eastern Church. Note how her soul is borne up to heaven by an angel too!