The Meaning of Advent

From a priest of the Institute of the Incarnate Word: Fr Daniel Vitz, IVE

This Sunday is the First Sunday of Advent. In order to aid our passage through this important liturgical season, we offer a meditation in advance of each coming Sunday. Each is written by a priest from the Institute of the Incarnate Word, IVE, and we are delighted that they have taken the time to do so. The first is by Fr Daniel Vitz. He writes:

Advent. All of us have heard the word many times before—we think of certain hymns, the wreath with four candles, and so on. Obviously, Advent is much more than the hymns we sing or the signs we use—but what is it? “Advent” comes from the Latin word, advenire, which means to “come to.” So, what is coming to us?

The first answer that springs to mind is “Christmas”—Christmas is coming. But Christmas is not a reason in itself—it is a reminder of something much bigger. What we recall during Advent is the coming not of Christmas but of Christ himself. We have all heard the term “the Second Coming”, but in Advent, first and foremost, we remember the “First Coming” of our Lord, Jesus Christ, into the world.

When we consider Advent, it is helpful to consider the circumstances that surrounded Christ’s first coming. We know that the Jews were God’s chosen people—a people set apart as being particularly His own. We know, too, that he made a covenant with them—first through Abraham and then through King David.

It was under David’s son Solomon that Israel enjoyed its greatest wealth and power and prosperity. At the height of its power, the Kingdom of Israel was the size of . . . Massachusetts. So it was never that big, or that powerful even at its strongest—that was never the nature of God’s promise to Israel. Indeed, even that strongest period only lasted for about 50 years—until about 900 BC—because after Solomon died, the Kingdom of Israel was divided into two kingdoms, Judah and Israel, each ruled by different kings. And as a general trend, the people of Israel continued to grow weaker over the centuries, not because God had forgotten them, but because the Israelites had forgotten God.

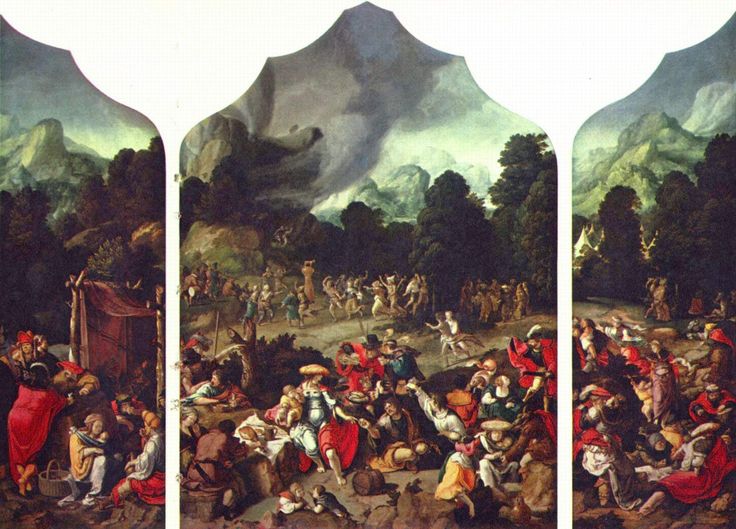

The Jews worshipped a golden calf during the Exodus from Egypt with Moses, and 1,000 years later they were still doing the same thing. Why?

First and foremost it was because they wanted to be like everyone else. Their neighbors—the Ammonites, the Moabites, the Edomites, the Egyptians—were all pagans, and they all worshipped things. And the Israelites, too often, just wanted to fit in—though they often didn’t even realize it—and so they increasingly brought this paganism (and all the wickedness that comes from paganism) into their lives and into their culture. They engaged in all kinds of sexual impurity, and they killed their own children to sacrifice them to idols. They even brought those idols and everything that came with them—the sacrifices, the impurity—into the Temple in Jerusalem—into the House of God that had been built by Solomon. The book of Kings says: “They followed worthless idols and themselves became worthless.” (2 Kings 17:15) God said to Isaiah, “Their land is full of idols; they bow down to the work of their hands, to what their fingers have made.” (Isaiah 2:8)

Almost all the people of Israel forgot their God—those who practised their Jewish faith seemed to care only about external things, and the majority turned their back on Him and served idols and they wallowed like pigs in their wickedness. And it was because of this that the people of Israel were laid low.

First, the Northern Kingdom of Israel was destroyed by the Assyrians and then the Southern Kingdom of Judah was destroyed by the Babylonians. The Babylonians ultimately destroyed Jerusalem and the Temple that had been defiled by the Israelites. We have to remember that for the Israelites, there was only one Temple—the Temple—and when it was gone, they had no center around which they could worship. Even more, both the Assyrians and then later the Babylonians took many, many of the Israelites away with them, leaving the land desolate.

God said that he would strike the Israelites and scatter them, in punishment for their wickedness—and he did that. But there was another element to the prophesying of Isaiah, and Jeremiah, and Ezekiel. This was the fact that God would never forget His people—that His covenant with them was everlasting.

Remember this, O Jacob, you, O Israel, who are my servant! I formed you to be a servant to me; O Israel, by me you shall never be forgotten.

What did that mean? Well, the prophets had made clear that there would be a messiah—someone who would come to save the people of Israel, because even if his people were unfaithful, God would always remain faithful to his part of the covenant. And some of those prophecies were pretty specific about when that would happen. They knew a number of details about what the Messiah would be like—he would be descended from the tribe of Judah, and in the line of King David, he would be born in Bethlehem from a virgin. But they also knew something about the time that he would be coming. In the years before Christ’s birth, the Jews believed that the Messiah would be coming at any moment. Among other things, they knew that according to the prophecies, the Messiah would come when the Temple had been rebuilt, and it was in fact just being finished by King Herod when Jesus came. At the time, almost everyone was expecting something big to happen. Surely that is part of the reason why King Herod instantly believed what the magi told him about the birth of the King of Israel, and why he immediately tried to put a stop to it.

There are two other characters we haven’t mentioned yet—the most important ones. First, Joseph, the husband of Mary and the foster father of Jesus. Consider what he felt being there at the birth of Jesus. Recall again where it took place—in a stable. Can you imagine how, as a man, as a husband, he must have burned with shame at not having been able to provide even a bed for Mary to have her baby? How could he not think that he had failed, when he had to allow his beautiful, perfect, sinless wife to give birth to the son of God in a stable?

![]()

It’s a good example of how mysterious God’s ways are, and how different they are from ours. In God’s wisdom, it was right that the Messiah should be born in a humble place, and yet Joseph could not have known that and probably reckoned himself to have failed. So too with us—we must always strive to do God’s will, and yet, we must also be willing to accept the difficulties that come across our path, knowing that God’s ways are not our ways and that those things beyond our power to change are somehow—mysteriously—part of God’s providence.

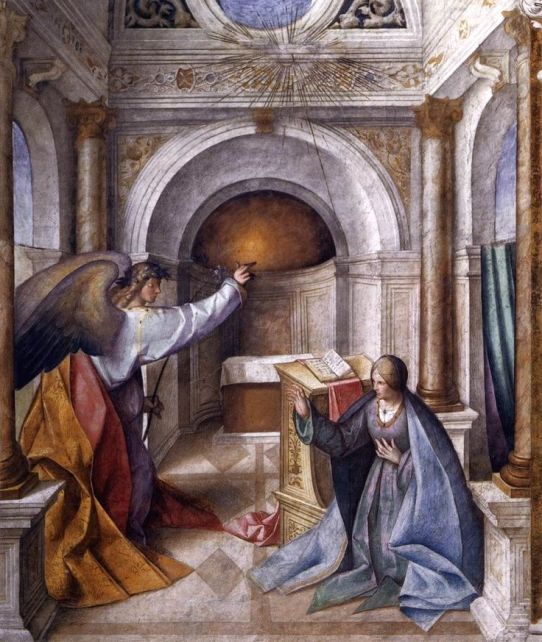

Finally, consider Mary. From the moment that the angel Gabriel came to her, she said, “Be it done unto me according to they word, I am the servant of the Lord.” She could not possibly have known the entirety of all that God would ask of her. It was far more than she could ever have dreamed, but she said yes to God, and God worked the greatest wonder in history through her—he brought us a Savior. Although Mary’s role in salvation history is absolutely unique, there is a lesson for us here too. We are each of us also called to something by God, something incredible, something marvellous. God wanted Mary to give him a human nature—Jesus Christ. And God wants each of us to give him a human nature too—John or Jennifer or whoever, because he wants to work for the salvation of souls through us. Each of us has a vocation, a calling from God. For some of us, it is to the married life, for others, it is to the priesthood and to the religious life. Whatever it is, it will be stupendous, but first, we have to say yes.

The Annunciation by Boccaccino, Italian early 16th century

Mary did say yes, and so today we can consider the meaning of the Advent of Christ. Advent, “coming”. Why do we say that Christ “came to” us? Well, that’s easy—because he did; he came to us. Well then, why did he come to us? Because we couldn’t go to Him. We were paralyzed by sin—St. Paul says that before Christ came, the whole world was “groaning under the weight of its sin.” We were paralyzed, and because of his infinite love for us, God condescended to become a man like us (“born in the likeness of a slave”) in order to save us. Think for a moment about what kind of humility that implies. God who is all powerful, all knowing, all everything that is good, became nothing—a bit of dust. Imagine loving someone so much that you would be willing to become a worm. And not just be a worm, but be a worm that is despised by all the other worms. Well, for God to become a man is infinitely more humbling than even that, because his infinity took on flesh—he was “born in the likeness of a slave.”

Now, we have been talking about the first coming of Christ, the first advent of Christ, 2,000 years ago, but obviously, this isn’t just history, it is a reality that still exists today. The first coming has already taken place, but what about the second coming? Most of us have heard the term “the Second Coming” before, but the second coming can be understood in two senses. The first is the one that we all probably know—that eventually, Jesus Christ is going to return to earth, not humbly and unknown as he did in Bethlehem 2,000 years ago, but in his glory and might, and he will judge both the living and the dead. We can have no idea when this will happen, and so we must always be prepared to face Christ—that is, always be careful to keep ourselves in a state of grace—since we never know A) when he will come again, or B) when we will be called from this world and die. The question of our own death relates to another sense in which some of the great saints have referred to the Second Coming. In this sense, the Second Coming is the advent—the coming—of Christ to an individual person, an individual soul. Each of us is a member of God’s chosen people; as members of His Church we have been baptized and become members of His mystical body. We are his elect, just as the ancient Israelites were; indeed, we are so even more than they were.

But the same problems that the ancient Israelites had, we also have. Sometimes, we just want to fit in, and just wanting to fit into popular culture will eventually lead us to evil, because the values of the world are not what God values. And so, like the ancient Israelites, we become idolaters. We are so tempted—and we so often give in to the temptations—to worship things. What things? Maybe not statues of goats, but money, and pleasure, and so on. We were made by God for God—to love and to serve Him—and when we lower ourselves to worship things beneath us, we despise God and we despise our own dignity—we despise a gift that God has given us, and we try to deny that God made us for himself.

But we are His. And he wants to come into our hearts to dwell, just as he came into this world in Bethlehem 2,000 years ago. Our hearts are pretty poor accommodations—there’s nothing five-star about us. God surely deserves to dwell in something much nicer than we can offer him. But we also know that—mystery of mysteries—he still wants to dwell in our hearts. And perhaps we shouldn’t be too surprising since we also know that from the beginning—from his first advent in that cave in Bethlehem—Christ has been accustomed to pretty simple, even unworthy places to stay. But that doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t still do everything we can to prepare our hearts for the coming of Our Lord. Really! Jesus Christ, who is God Himself, has come to earth to redeem us. He was born of the Blessed Virgin Mary, suffered, died and rose again to give us new life, but before leaving, he gave us the sacraments—he gave us the Eucharist, he gave us Confession.

And so that advent of Christ 2,000 years ago was not just a moment in history—isolated. It matters now because there is a second coming of Jesus Christ to our souls. Today, and this Sunday, in every and any mass, Jesus Christ will be really present—body, blood, soul, and divinity—on the altar. The same Jesus Christ that Mary received into her womb, the same Jesus Christ that the wise men adored in the manger, the same Jesus Christ Herod tried to kill, and the same Jesus Christ who gave his life up for us on the Cross. That same Jesus Christ will be really present on the altar and will come to dwell in us when we receive the Eucharist. We will never be the type of accommodations that Our Lord deserves—we’re more a stable than a palace, but the least that we can do is clean that stable—sweep it, and make sure that the manger where we are going to place our Lord has clean hay in it. That is, let us make sure that we repent of our sins, confess them, and guard our hearts from the world so that we will be as worthy as we can be to receive Jesus when he comes to us in the Eucharist.

Beautiful. Thank you Fr Vitz.

LikeLike