I attended a talk on healthcare at Star of the Sea Catholic Church in San Francisco last week given by Pontifex University professor, Dr Michel Accad. Much of the talk was devoted to consideration of the options that Catholics have for affordible healthcare. He spoke in detail about sharing ministries (such as Samaritan); and how many general practitioners are structuring their practices in a new way so that they are employed directly by the patient and act as their advocate. This is in contrast to the usual arrangement where the doctor effectively becomes an agent who sells treatments and drugs for the providers to the payer, who is not the patient, but the insurance company. In his new model, in contrast Dr Accad is motivated to act on behalf of the patient first, and so is an advocate for him, striving for example to bring down the cost of treatments and drugs by negotiating with pharmaceutical companies. He is also able to devote much more time to their care. Furthermore, it enables him to offer treatment that is in accord with Catholic social teaching.

He opened up his talk by asking the question: who here thinks healthcare in this country is going well? No hands went up. He then described how it is possible to have healthcare options that allow for the flourishing of the patient as a human person – body, soul and spirit – and a relationship between doctor and patient that is fruitful for both patient and care provider. In the Q &A session afterwards, it became apparent from the discussion that this was of interest not only to currently disgruntled patients but also to doctors who are frustrated that they cannot give the sort of treament they would like to give. Several spoke of this frustration under the current system.

Dr Accad is a medical doctor (qualified both as a general practitioner and as a cardiologist) who is able to take a broad view of the crucial issues involved. He is one of those rare people who is simultaneously able to analyse the details and to synthesise it all into the big picture. A committed Catholic he writes about medicine and is published in peer reviewed medical journals; he writes about the philosophy of nature and philosophical anthropology and has been published in The Thomist; and he has delivered papers on the economics of healthcare at the Mises Institute. He also has a popular blog on how these issues impact the medical profession called Alertandoriented.com.

Of course, I was interested in the details of how one might have access to affordible health care that is aligned with Catholic social teaching and imbued with genuine consideration of the patient as a person (and if you are interested in this I suggest you contact him through his blog, here). But aside from that what I found fascinating what his description of how so many of the problems associated with healthcare today, even before Obamacare, eminate from a dualistic understanding of the human person as a physical body occupied by a thinking soul; rather than a profound unity of body and soul as a single entity. This is not a bad thing in itself, a deep understanding of how the physical function fo the body work as has lead to great strides in medicine; but it does place limitations on the scope of treatment through a neglect of the happiness of the person and his spiritual needs. If the underlying problem is spiritual, for example, while treatments might cause the physical symptoms to be alleviated, physical ailments might resurfacing in other forms.

And it runs even more deeply than that. Without a clear picture of what human person is, the idea of a health as a goal for treatment is not clearly defined either. This has lead over the last 100 years or so, to the creation of a ‘health market’ which has been engineered to serve that idea of a human being as machine – as an object to be repaired; rather than as a person who needs health in order to direct his activity towards his ultimate end, which is union with God. Consequently, the patient occupies a role in this financial model that is more akin to the car in the repair shop, in which the insurance company is the car owner and the doctor is the mechanic. While this model might work well for cars, when the doctor’s surgery becomes a glorified human ‘body shop’ the misalignment and conflict of interests and goals leads to secondary (and more) problems in health care. As soon as the current system, under the guidance of government began to be introduced in the early 20th century, it caused escalating costs because there is no incentive for the key players to keep costs down on behalf of the patient. The doctor seeks to serve first the specialist treatment providers, pharmaceutical companies and insurance companies, rather focussing primarily on the improvement and maintainance of the health of the patient (however we define the word).

Those who wish to know more about the connection between the structuring of the health market and anthropology might be interested in reading (or listening) to Dr Accad’s talk on the subject given to the Mises Institute last year, which can be accessed via his blog, here: From Reacting Maching to Acting Person.

Dr Accad is currently preparing material for his first course for Pontifex University on the Philosophy of Nature and Philosophical Anthropology. He is a wondeful addition to our faculty precisely because of his ability to draw themes from one area of expertise into application in another. This ability to think synthetically is what the whole education at Pontifex is devoted to, and it is why a formation in beauty is right at the heart of what we do. When one apprehends the beauty of something , one is able to see not only how it’s parts are in right relation to the others (due proportion); but also how the whole is in accord with its purpose and in right relationship with all that surrounds it (integritas). In short one is able to look at the detail (analysis) and place it in the bigger picture (synthesis). This is why beauty and culture (which touches every aspect of human life, including economics and health provision) are so intimately related.

As Catholics we must strive always to take that mental step away from whatever field of study we are engaged in and ask ourselves the big question – how does this relate to man’s goal of union with God through worship of Him in the heavenly liturgy, in the next life, and the earthly liturgy in this.

We will hear more about the work of Dr Accad in the future!

St John of God, by Murillo (Spanish, 17th century).

Afterword: St John of God, (1495 – 1550) was a Portugese born soldier who founded a hospital in Granada, Spain and whose followers later formed the Brothers Hospitallers of Saint John of God, dedicated to the care of the poor, sick, and those suffering from mental disorders.

How many doctors today are taught of the need for God’s grace in their work for the benefit of both patient and doctor, I wonder? One only has to look at the design of hospital buildings past and present to see how differently the provision of care was considered. Below are photographs of the exterior and interior of the Hospital de Tavera, Toledo, Spain, built in the 16th century (which today is a museum housing many El Greco paintings):

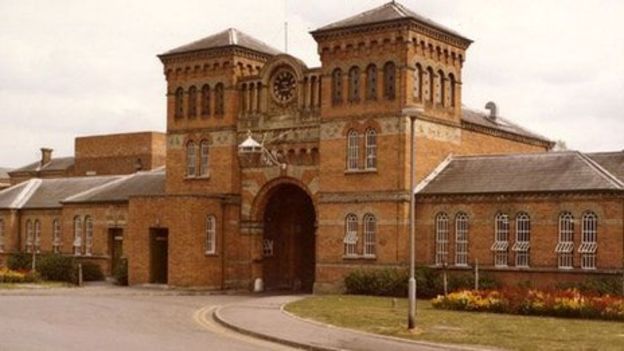

and here is a standard National Health Service hospital building, in Darlington County Durham in England:

The standard criticism of the modern building is that it is only designed for utility, hence its depression appearance. I would argue something different: in my opinion beauty does have a utility, which is to raise hearts and minds to God. That is when a hospital is building is beautiful, it’s beauty helps serve the spiritual needs of tall the people in the care community it houses, and for good of all concerned. Furthermore, just as the person is a profound unity of body and soul, the hospital should be a profound unity of design that aids the function of restoring the health of the all aspects of the human person. Such a hospital will be beautiful and will optimise its functionality of the provision of both spiritual care and physical care. It is no accident that the hospital, just like and educational institution built in this time, has the look of a monastery. Both institutinons have aims that cannot be separated from the supernatural end of the human person and both aim to engender a community in which all work toward this end for themselves and others.

Here’s another example, Broadmoor Hospital was purpose built as a prison for criminally insane and houses some of Britains most violent and notorious convicted criminals.

Those who are committed to its care are almost certainly going to live the rest of their natural lives behind its walls. The original building was completed in the mid-19th century. It does not have the cloisters and prayerful feel of the 16th century Spanish hospital, I suggest, but nevertheless it is a listed building. The prison/hospital is currently being redeveloped and there has been discussion as to what use the original building will be put to. Newspaper reports suggest that one suggestion is to turn it into a luxury hotel. While I am sure that it was not pleasant to be an inmate there, it seems that in some ways our Victorian forebears had greater insight about the need for the care of the souls of the most reviled members of society than modern society and how to do it.

The Darlington hospital no doubt has dedicated staff and patients receive the best that the National Health Service in the UK has to offer and the National Health Service has its problems too for similar reasons at root, although manifested in different ways (It is interesting to note that while the quality of care in many measures is not a good as that offered by the America system, satisfaction of patients is based upon anecdotal evidence, higher). Regardless, the design of the building tells us something about how the human person who is to be treated is viewed, I suggest. I would argue that it is not even the optimal design if the provision of physical care, for the physical and spiritual cannot be separated. The building of beautiful hosptials is not an extravagance, but ought be considered a necessity that will give us the most highly functional hospitals by any measure. As we can see through Dr Accad’s discussion of the provision of healthcare, care of body and soul cannot be separated, just as body and soul cannot, in reality, be separated in the person being cared for.

Neglecting the spiritual aspects of man will almost certainly affect detrimentally the care of even man-as-machine in ways that cannot always be anticipated. Let us be clear. Wrong anthropology does not suddenly invalidate modern medicine or its methods. It simply allows to locate the source of the problems that remain with the recognition there is more to be done. Once we recognize that man is a single entity that is both physical and spiritual who is made to worship of the God in the sacred liturgy and that this is the activity that all others are ordered to in this life, then we have the greatest chance of restoring all aspects of human health (and having beautiful hospitals once again!).