This is the second in a series of six, to see the article in full go here.

1. Scripture

I have recently attended a series of online scripture courses that are designed to connect the traditional imagery of the Church to its scriptural roots and to the liturgy. This has been an eye-opener for me. The books that the course relied upon, apart from the Bible and the Catechism were, The Bible and the Liturgy by Fr Jean Danielou; and Baptismal Imagery in Early Christianity by Robin Jensen and the Cathechism of the Catholic Church.

As part of that course it became clear to me that there is a need for general re-ordering of the rites of initiation so that Baptism, Confirmation/Chrismation and their culmination in the Eucharist are understood and connected in people’s minds. It will be difficult to create a pattern of art ordered to these, if their meaning is misunderstood by most people who go through it because of this misplaced order. We have just heard about how this change was instituted in the Manchester NH diocese by His Excellency, Bishop Libasci. I understand that there are now 11 dioceses in the United States which have done this.

Also, it seems to me, these rites would be better done in connection with regular Sunday liturgies rather than quietly on a Saturday morning. (as they still are for adults at the Easter vigil), Then the whole community of the parish will welcome a new member into the body of Christ and be re-catechised each time these and the Mass are celebrated. This is how an effective and ongoing mystogogy – a deepening of the mysteries – might happen.

The art will teach people about the meaning of these sacraments by giving a pictorial commentary on what is happening and for much of this, scripture will be the source. There is hardly a passage in the Old Testament that in some way doesn’t anticipate what happened in the New, and there is so much of the New that relates in some way to these three sacraments.

It is often said that the images of traditional churches, for example the stained glass windows of gothic churches, and were intended as scriptures in images – effectively Bible lessons for those who cannot read. I doubt this. Images in churches should be chosen not to direct our attention to the Bible, but rather to focus our attention on the liturgy. The goal of art in a church is to give understanding about what happens in the church primarily – the worship of God. Certainly many of the images are rooted in scripture, and those who understand what they are seeing would know and understand scripture too; but art reflects scripture, because the Bible is, fundamentally, a liturgical document. It was written to be read in the context of the liturgy and it contains the blueprint for the sacraments and the Christian life which is lived in its fullest in the liturgy. The scriptural art is in church, therefore, not to instruct us in scripture as an end (unless you are protestant). Rather, it is to offer an alternative account of the same truths which are in the Bible and are relevant to the liturgy.

And that is why see in addition many images which are liturgical, but not scriptural. For example the many of the images of saints such as those referred to in the Roman Canon or whose feast days are celebrated. Their presence through the year tells us that they are worshipping with us in the heavenly liturgy and reflects the pattern of feasts and commemorations within the liturgical calendar when they will be a focus for prayer. Also images relating to many feasts are a visual accounts of a theology which is more than a strict narrative of a biblical passage and will be derived from other aspects of Tradition as well.

This being so, one might ask why do I stress scripture so strongly ,why not just catechise directly on the meaning of the liturgy? The answer lies in identifying our worship as a living out of the story of salvation that scripture tells. As mentioned a couple of weeks ago, I recently read Fr Robert Taft’s book, The Liturgy of the Hours in East and West, in which he makes the point that in order to profit from praying the liturgy as a whole, including the Hours:

…one must be a person who prays and whose life is penetrated with the Scriptures. The Bible is a story of God’s ceaseless calling, drawing, gathering and of his people’s constant waywardness. And the Fathers and monks of the early Church, in their meditation on this ever-repeated story, know that they were Abraham, they were Moses. They were called forth out of Egypt. They were given a covenant. They knew the wandering across the desert to the Promised Land was the pilgrimage of their life too. The several levels of Israel, Christ, Church, us, are always there. And the themes of redemption, of exodus, of desert and faithful remnant and exile, of the Promised Land and the Holy City of Jerusalem, are all metaphors of the spiritual saga of our own lives. (p. 371)

In my opinion it has been the general inability of creative Catholics to connect this grand drama that is revealed in scripture and the liturgy to each personal story lived out by non-Catholics in wider society that is so much of the cause of the general separation of contemporary culture from the culture of Faith. This divide is described by Benedict XVI in the Spirit of the Liturgy and if we are to accept his analysis, has existed for about 200 years at least.. Every aspect of human activity and hence the culture can potentially be penetrated, to use Taft’s word, by the scriptures but people can’t give away what they haven’t got. Artists, dramatists, composers and writers need to be catechised so that they grasp this and are able to infuse their work, albeit obviously or subtly, with this message so that it connects with those whom we wish to evangelize.

Within the books of the Bible, there should be a special emphasis on Genesis:

Among all the Scriptural texts about creation, the first three chapters of Genesis occupy a unique place. From a literary standpoint these texts may have had diverse sources. The inspired authors have placed them at the beginning of Scripture to express in their solemn language the truths of creation – its origin and its end in God, its order and goodness, the vocation of man, and finally the drama of sin and the hope of salvation. Read in the light of Christ, within the unity of Sacred Scripture and in the living Tradition of the Church, these texts remain the principal source for catechesis on the mysteries of the “beginning”: creation, fall, and promise of salvation.(CCC 289)

Artist, patrons and priests, therefore, must understand the ultimate end of both scripture and holy images in the liturgy. When this is done then the church can be adorned, floor to ceiling (including both floor and ceiling) with images that are united to the worship of God. There is no distraction if it is all derived from and points to the liturgy. There is a place for non-liturgical, devotional art, too, but it should never be such that it dominates or detracts from that which is directly connected to the liturgy. It was the overabundance of devotional imagery in the period before the Council, I suggest, that led to a desire to strip much of the art away. Unfortunately this was overzealously implemented!

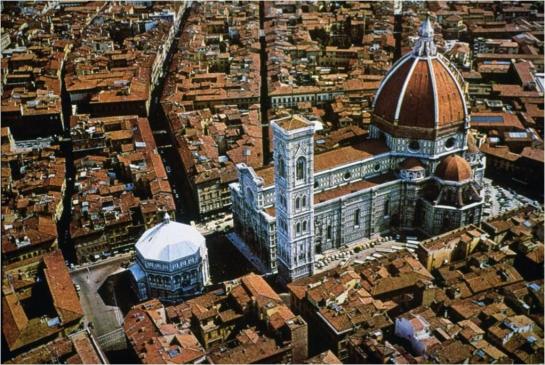

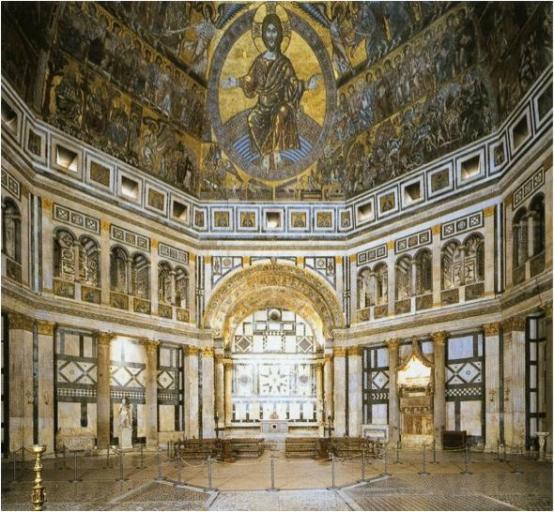

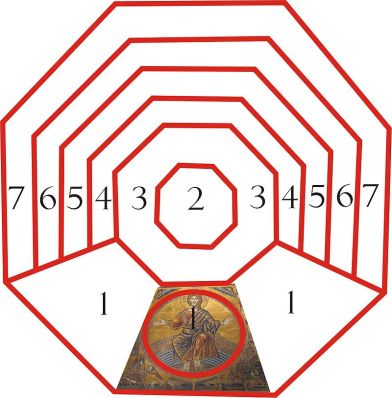

In regard to the place of scripture, consider the schema for the baptistry in Florence for example. It is Romanesque, built in the 11th and 12th centuries. The building itself is octagonal which reflects the symbolism of Christ as the 8th day of creation. It is adorned with sybolic geometric art and in the interior the dome has a complex schema that reflects the bibilical types of the sacrament.

Plan of the mosaic ceiling : 1. Last Judgement. 2. Lantern. 3. Choirs of Angels. 4. Stories from the Book of Genesis. 5. Stories of Joseph. 6. Stories of Mary and Christ. 7. Stories of St. John the Baptist.

This is only part of it, for the doors of the Baptistry – perhaps even more famous than the building they were made for – also reflect a whole series of scenes from the Old and New Testament. You can read about this on the Wikipedia entry for the Baptistry, from which all the above images come from. There is more information on how baptistries in the early Church were decorated from Robin Jensen’s excellent book Baptismal Imagery in the Early Church.

I do not suggest that the baptistry should always be a separate building, but it should at least be a separate place, perhaps close to the entrance of the church, so that after baptisms there might be, perhaps, a procession to the main body of the church building.

There are equivalent types and narratives rooted in scripture that could be the basis for imagery for Confirmation – for example those relating to the Holy Spirit; and to the Eucharist as well and these, especially the latter, should adorn the main body of the Church.

Continued tomorrow….