Understanding that man is body, soul and spirit might be a step towards establishing a culture of beauty.

I have written before, here of the idea that liturgy and culture are linked. Each forms and reflects the other. If this is the case, then the answer to the question of how to reform a culture of ugliness, even a culture of death in any lasting way has its roots in, or at least must include firmly at its heart, liturgical reform.

A true Catholic culture is one that not only reflects the liturgy but through its compelling beauty, is so powerful that it overcomes other cultures and dominates the profane (ie the wider culture outside the domain of religious practice). This is the case with the gothic and the baroque. All art, architecture, and music during these periods, for example, seemed to be drawing on the forms that were set in the liturgy. In his book The Spirit of the Liturgy, Pope Benedict XVI says the following: ‘The Enlightenment pushed the Faith into a kind of intellectual and even social ghetto. Contemporary culture turned away from the Faith and trod another path, so that faith took flight in historicism, the copying of the past, or else attempted to compromise, or lost itself resignation and cultural abstinence.’

A true Catholic culture is one that not only reflects the liturgy but through its compelling beauty, is so powerful that it overcomes other cultures and dominates the profane (ie the wider culture outside the domain of religious practice). This is the case with the gothic and the baroque. All art, architecture, and music during these periods, for example, seemed to be drawing on the forms that were set in the liturgy. In his book The Spirit of the Liturgy, Pope Benedict XVI says the following: ‘The Enlightenment pushed the Faith into a kind of intellectual and even social ghetto. Contemporary culture turned away from the Faith and trod another path, so that faith took flight in historicism, the copying of the past, or else attempted to compromise, or lost itself resignation and cultural abstinence.’

In other words, by the 19th century and as a result of the Enlightenment, the culture of faith was separated from the wider culture. Catholic culture, as it was manifested at this time, was not a genuinely Catholic culture of beauty, but rather an emasculated, paler version. In the area that I know well, art, we see this very clearly. There are some exceptions, but in general, the academic art of the 19th century is only a poorly defined shadow of the 17th century baroque from which it is descended. For those who are interested to know more, you might read for example articles here and here or for a fuller account read the book Baroque by John Rupert Martin.

To give you sense, look for yourself. The paintings below are St Paul by Velazquez, the Baroque master;

and by Ingres, the star of the 19th-century French Academy, which in comparison, to my eye, is sterile, cold and clinical:

If we accept the premise and this assessment of the culture, then it indicates that in the 19th century there were problems with the liturgy as well as the culture. This would explain why the response to the Enlightenment in this period was not only intellectual but also liturgical, with the beginnings of a liturgical reform movement.

This being so, the question remains as to what it is about the Enlightenment that affected the liturgy? There is a helpful essay in a booklet called Looking Again at the Question of the Liturgy with Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger: the Proceedings of the July 2001 Fontgombault Liturgical Conference, edited by Alcuin Reid. One of the presentations was by the late Stratford Caldecott called Liturgy and Trinity, Towards a Liturgical Anthropology. In this, Mr. Caldecott argued that the problems lay in the fact that the anthropology – the understanding of the nature of man – had strayed from a full recognition of the spirit as part of the anthropology described by scripture. St Paul, for example, talks of body, soul, and spirit. There had been tendency argues Caldecott, to equate, or at least insufficiently differentiate between (in our understanding), soul and spirit. (To read this online, go to the link here; in the left-hand column click ‘Online Reading’; scroll down the articles by Stratford Caldecott and you will see the essay title.)

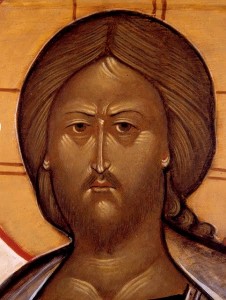

His description of the ‘spirit’ is most interesting. Equating it with the intellectus of the Western medievals or the nous of the Eastern Church in the tradition of Church Fathers, the spirit is the spiritual receptive knowing power of the human mind. This is the aspect that ‘sees’, so to speak, God and is receptive to grace. The use of the terminology can vary from person to person and this can be confusing sometimes, for me at least, when trying to understand these things. One thing that the Catechism is clear on as that talk of the spirit, which is non-material and spiritual in nature, does not introduce a  duality into the soul. So man is a profound unity of body and soul and this describes the human person. The spirit is the higher part of the soul or as I once heard it described, the ‘soul of the soul’. It that part that is closest to God, the portal for grace which pours out from God, transforming us (transfiguring) into the image and likeness of Him. While the fathers do therefore sometimes use the word soul interchangeably with a description of the full spiritual dimension of man that includes the spirit, the distinction of the two in the minds of the medievals, it seems, is not lost either. Occasionally in icons, the artist paints a ‘bump’ on the forehead. I was told that this shape drawn in the forehead, between the eyes, is sometimes considered a physical manifestation of the spiritual eye, the nous. (See the icons displayed here.)

duality into the soul. So man is a profound unity of body and soul and this describes the human person. The spirit is the higher part of the soul or as I once heard it described, the ‘soul of the soul’. It that part that is closest to God, the portal for grace which pours out from God, transforming us (transfiguring) into the image and likeness of Him. While the fathers do therefore sometimes use the word soul interchangeably with a description of the full spiritual dimension of man that includes the spirit, the distinction of the two in the minds of the medievals, it seems, is not lost either. Occasionally in icons, the artist paints a ‘bump’ on the forehead. I was told that this shape drawn in the forehead, between the eyes, is sometimes considered a physical manifestation of the spiritual eye, the nous. (See the icons displayed here.)

A quote from Joseph Pieper’s Leisure the Basis of Culture (p11-12) was helpful to me here: ‘The medievals distinguished between the intellect as ratio and the intellect as intellectus. Ratio is the power of discursive thought, or searching and re-searching refining and concluding, whereas the intellectus refers to the ability of ‘simply looking’ (simplex instuitus) to which the truth presents itself as a landscape presents itself to the eye. The spiritual knowing power of the human mind, as the ancients understood it, is really two things in one: ratio and intellectus: the act of knowing involves both. The path of discursive reasoning is accompanied and penetrated by the intellectus’ untiring vision, which is not active but passive, or better, receptive – a receptively operating power of the intellect.’ It seems that the intellectus here could be identified with the nous or spirit.

Without a full acknowledgement of this tripartite anthropology, suggested Caldecott, a flawed dualism consisting only of body and soul is created and an instability in which one of the aspects tends to dominate the other to the exclusion of God (just as Cartesian dualism was inherently unstable and led in two very different directions: materialism and idealism). According to trinitarian anthropology, the human person is by its very nature other-centered. We love God, and this opens us to the life of the other; we love our neighbor, and this opens us to the love of God. Without fully appreciating the spiritual faculty of the soul we cannot properly understand either marriage (based on the self-giving love of man and woman) or the Mass (the marriage of heaven and earth). Thus the crisis over Humanae Vitae in the 1960s was paralleled by the crisis over reforms in the liturgy because both had the same root — an earlier loss of the sense of the spirit uniting husband and wife in openness to new life on the one hand, and of the spirit uniting priest and laity in one single work of sacrifice on the other.

To those who had acquired this mentality, it seemed that the Mass had become an exercise in which the priest did his thing at the altar and the laity waited and watched or prayed their rosary in the pews. This is why there was also, more recently a reaction that went to the other extreme by over-stressing “activity” in the Mass, along with human fellowship and social justice, as though these were the only things that were important. Many religious orders went into steep decline as the communitarian aspect of their mission took precedence over the liturgical, the love of neighbor over the love of God. It is the spirit in man that opens us to the “vertical” dimension of grace: without it, both marriage and the liturgy are reduced to activities performed on the horizontal plane, with little or no relationship to heaven.

It strikes me that such a neglect as a result of the Enlightenment should result in a cultural decline as well as a liturgical decline is made all the more understandable when one considers the role of the intellectus, or spirit, in the apprehension of beauty. In the first part of her little essay Beauty, Contemplation and the Virgin Mary, Sister Thomas Mary McBride, OP describes succinctly in just a few paragraphs, the traditional understanding of beauty and how man apprehends it (and as such I would recommend this piece for anyone seeking an introduction to this subject). She draws on the Latin medievals and states that beauty illuminates the intellectus, describing the apprehension of beauty as the ‘gifted perfection of seeing’. Then echoing Caldecott in the connection between intellectus and spirit says: ‘In the light of the above, this writer would suggest that the proper place of beauty is in the spirit.’

An appropriate active participation in the liturgy is one that engages the full person in order to encourage within us the right interior disposition. Any participation in the liturgy that does not engage body, soul, and spirit, therefore, does not engage the full person. Our participation in the liturgy is the primary educator in the Faith at all levels. A true conformity of body, soul, and spirit is what is desired. One can see that any participation in which consideration of the spirit is neglected (through a balanced active participation of soul and body) will result in therefore necessarily result in a deficiency in our ability to apprehend beauty, which resides in the spirit. This explains this link between culture and liturgy and how important liturgical reform is in our efforts to create a culture of beauty today.

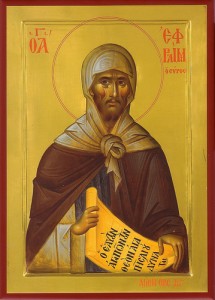

St Ephrem the Syrian who lived in the 4th century AD in modern-day Turkey is a Doctor of the Church and one of the Church Fathers referred to by Pope Benedict XVI in one of his weekly addresses and whom he encouraged us to read. St Ephrem wrote the following in the 9th of his Hymns to Paradise:

Far more glorious than the body is the soul, and more glorious still than the soul is the spirit, but more hidden that the spirit is the Godhead.

At the end, the body will put on the beauty of the soul, the soul will put on that of the spirit, while the spirit shall put on the very likeness of God’s majesty.

For bodies shall be raised to the level of souls, and the soul to that of the spirit, while the spirit shall be raised to height of God’s majesty;

Saint Paul, in 1Corinthians 2:11 says: “For what man knoweth the things of a man, save the spirit of man which is in him? even so the things of God knoweth no man, but the Spirit of God.” He makes a distinction between the “spirit of man” and the “Spirit of God” The spirit of man is that part of us that instinctively knows the things of how to be human, and is there from birth. The Spirit of God comes to us from our vertical interaction with Christ and gives us additional insight which would not ordinarily be there. Faith or unconditional trust in Christ is what opens us up to His Spirit. This article appears to take a different approach.

LikeLike

I think it does. Where does your interpretation come from? I’m wondering are you speaking from the disagreement over the natural desire for the supernatural, if I can put it that way, that existed in the mid-20th century between the Garrigou-Lagrange and Henri de Lubac? I would say that I am in the latter stream. It seems to me that you are in the former? Or are you coming at it from a completely different place? If however, you are coming from the Catholic nature/supernature dispute, perhaps you have read The Mystery of the Supernatural by de Lubac and published by Ignatius. I found this convincing.

LikeLike

My interpretation comes from my take on Scripture. I believe that we have a natural inclination towards wanting peace and contentment in life. Because this ultimately comes from our connection with God, it is an indirect seeking of the supernatural; but what usually happens is that we naturally tend to look for peace and contentment in the natural realm through self-gratification. I found that I needed to be taught that this comes from God. I didn’t naturally think of it myself. Maybe this is why the Bible says that faith comes from hearing the word of God.

LikeLike

This is the question, does the desire for God only awaken when we hear scripture, or is it there already? I would point to the many people who have never heard scripture and yet believe in God, including non-Christians. How you explain their faith in your system I wonder? I believe that there is a natural revelation (eg the cosmos) as well as a supernatural and the former leads us to God as well. Scripture seems to confirm this eg in the psalms: the heavens proclaim the glory of the Lord.

LikeLike

Also..the Canticle of Daniel is powerful for me, especially when I sing it as part of the Church’s liturgy. This is another scriptural indication that God is revealed through his works?

LikeLike

I agree that nature points to belief in God; but does it tell us how to relate to Him and acquire His presence within us?

LikeLike

No, but it is natural to man to do so and he does so without scripture. Certainly, not in a fully Christian way – there are mysteries that are only revealed through the person of Christ (which is through the truths preserved by His Church and which includes scripture). The virtue of religion is natural to us and, I suggest, would express itself even without supernatural revelation. The virtue of religion is an aspect of justice and the highest virtue. My evidence for this is that prayer and worship occur in non-Christian societies. Nature doesn’t tell us directly to worship God, but when man reflects upon what nature does tell us, then in many cases even without scripture, he does pray and worship. Incidentally, there are some who do read and acknowledge scripture who misinterpret it and do not worship. This is why the Church is so important as the interpreter of scripture, and as the source of the full Tradition handed on to us by Christ, which includes more than that which is contained within scripture alone, I suggest

LikeLike

There is another option of how to relate to God besides prayer and worship, and it is called humility. The best definition that I have found for this humility is in 1Peter 5:5-7 which says: “be clothed with humility: for God resisteth the proud, and giveth grace to the humble. Humble yourselves therefore under the mighty hand of God, that he may exalt you in due time: Casting all your care upon him; for he careth for you”. I call this surrender and self abandonment. This is something that I was never taught in my Catholic upbringing and schooling. The only place that I found it was in the Bible. This is what made Christianity practical for me. Before this I was agnostic for a period of time, and before that, a doubter.

LikeLike

I agree humility is important and there are many things that are only available through supernatural revelation – these are the mysteries of the Faith. It’s a shame you had a poor Catholic education which didn’t reflect the teachings of the Church and so now you are just left to interpret the Bible in an idiosyncratic and personal way. You might try the Catechism of the Catholic Church if you haven’t looked at it. That tells us that for a Christian, the highest form of relation to God is in the liturgy (which one should approach with an attitude of humility) and the bible itself brings this out as well as Tradition and the Magisterium of the Church. There is a book called the Bible and the Liturgy by Danielou that outlines just how it is a document that is intrinsically liturgical – much of it was written to be presented within the liturgy and it contains the blueprint for the worship of God, as the Church has always done it.

LikeLike

What I discovered is part of Catholic teaching. The Church compiled the Bible in the fourth century as its primary source for Catholic teaching. Vatican II’s Dei Verbum 21 says: “Therefore, like the Christian religion itself, all the preaching of the Church must be nourished and regulated by Sacred Scripture”.

Until the printing press, the Bible was not widely available to the masses. Now it is. This was not anticipated by the Church in the fourth century. This is now a reality that has had the effect of decentralizing Christianity. The Church has had a difficult time in trying to manage this. It still prefers that Catholics read the Bible with the Catechism in hand.

LikeLike

I was educated by Salesians, Christian Brothers, and Jesuits who did reflect the teachings of the Church. The liturgy was always emphasized. The Bible was written to be presented in the liturgy and also elsewhere. It has a wider application and use, as I eventually learned to my amazement; it is also for our personal use. There is no need to restrict it; but it can be abused, just like anything else.

LikeLike

Well, the things you ‘discovered’ are part of Catholic teaching too, you don’t seem to understand the Church, it seems to me.

LikeLike

That’s interesting, my discovery is that the Church is fully scriptural and allows for much personal interpretation. However, whenever my personal interpretation differs from the Church, I defer to the Church because scripture tells me to do so – St Paul tells us that it is the Church that is the pillar of truth. So my interpretation and of history is in accord with the Church. Clearly, you have a different interpretation of scripture. The question then, if we have two different interpretations, yours and mine, how do we decide who is right? The only authority that I see referred to in scripture (you may differ) is the Church. Furthermore, the greater question for me is why does this matter? Well for me this is about happiness, and as a protestant who converted to Catholicism about 25 years ago now, the Catholic Church offers me the fullness of truth and the greatest chance of happiness in this world and the next.

LikeLike

Paul makes an interesting statement in 2Corinthians 1:24: “Not for that we have dominion over your faith, but are helpers of your joy: for by faith ye stand.”

Vatican II’s teaching on personal conscience and how we receive truth seems to apply here. If we have two different interpretations, it seems like we both need to go with our own interpretation even though one or both may be erroneous. Personal guidance of the Holy Spirit is also involved in this.

Happiness is an interesting subject. My peace and contentment (happiness) come directly from my relationship of trust in Christ. No organization can provide this. It can only point you to Christ. If the organization doesn’t do this, you may notice it in the Bible if you happen to see it on your own.

I don’t find any tidy answers for any of this. There were divisions in the New Testament Church, and there are divisions today.

LikeLike

. This is a not a fair reflection of the ‘teachings of Vatican II’ as I am aware of them (which I think actually is the idea that comes first from Newman about the importance of personal conscience). The Church and Newman should be allowed to say what they meant, and it is not what you are saying. There is a lot of your personal interpretation of scripture that I don’t share – in fact, I don’t see that it is scriptural at all, although I believe that you are sincere when you say that you believe that it is. Also, it simply doesn’t correspond to my own experience of what makes me happy. I tried the protestant approach and it didn’t work for me. I became Catholic because the Catholic Church is the Church of scripture more than any other and it gives me the happiest life. And I do believe that no one goes to heaven except through the Church, the mystical body of Christ. I’m not sure there is much point in discussing further? I will give you the last word and then will not respond. I would like to thank you for taking the time to engage with this.

LikeLike

We had an interesting discussion.

LikeLike