Using the example of the School of St Albans, I have been discussing how one might re-establish a tradition of sacred art for the Roman Rite in such a way that it might have the same success as that of the re-establishment of the iconographic tradition in the Eastern Church in the mid-twentieth century.

Stylistically, I have opted for something based upon the St Albans school, but for a canon of imagery I would look first to that of the iconographic tradition. This is because so much of the hard work has already been done. The figures of last century catalogues the a series of images that are rooted in scripture and related directly to the liturgy. So many of the great feasts have their own icons and we can re appropriate this for our own imagery. I say ‘so many’ because there are occasional differences between the feasts of the Roman and Byzantine Rites; so we might have to look to past examples in others styles as a source for content for these, and perhaps even in some cases develop a new iconography drawing upon the magisterium, scripture and tradition.

An example of this, I would be the Immaculate Conception which began, as I understand it, as a celebration of the Conception of the Mother of God on December 9th but was moved when adopted by the Western Church to December 8th in the latter part of the first millennium.

The familiar iconography of the Immaculate Conception is particular to the Roman Church and was developed in Spain in the 17th century and so is not part of the iconographic tradition. Francisco Pacheco (1564-1644) who was the teacher of Spanish baroque masters Alonso Cano and Velazquez (he was also Velazquez’s father-in-law), described the iconography of the Immaculate Conception in his influential book, The Art of Painting (Arte de la Pintura) published posthumously in 1649. I have written about this in some detail in my book, the Way of Beauty. The example below is by the great 18th century Italian painter Gianbattista Tiepolo.

So in my new style, I would adopt the content of the above picture, while trying to paint it in the style of the School of St Albans.

Iconographic or Gothic?

For ease of consistency as the tradition develops (being optimistic about it catching on!) I would stick to the principles of the iconographic prototype. Again this is something that is well thought out and can be a useful guideline. So for example, I would I would make sure that the compositions do not having saints in profile, and take care to eliminate depth so that the action, so to speak, takes place in the plane of the painting.

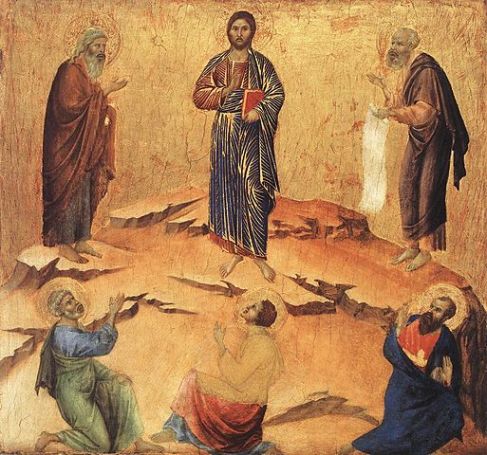

It can be surprising, sometimes, how following the principles can dictate how you design an image. For example, if every saint is to have a halo, then it is difficult to have images arranged packed together one behind the other as we see here:

In the following painting of the Last Supper, the artist Duccio wanted the viewer to be able to see the artifacts on the table, so omitted the halos in the figures in the lower part of the painting:

The iconographic prototype would not permit this so the artist below, in a modern icon, has arranged the figures so that none obscure the table.

Similarly, I would not want figures in profile. In the painting below, Duccio, again wants the central figure at the bottom, St John, to be looking up Christ and so has had to turn his head around.

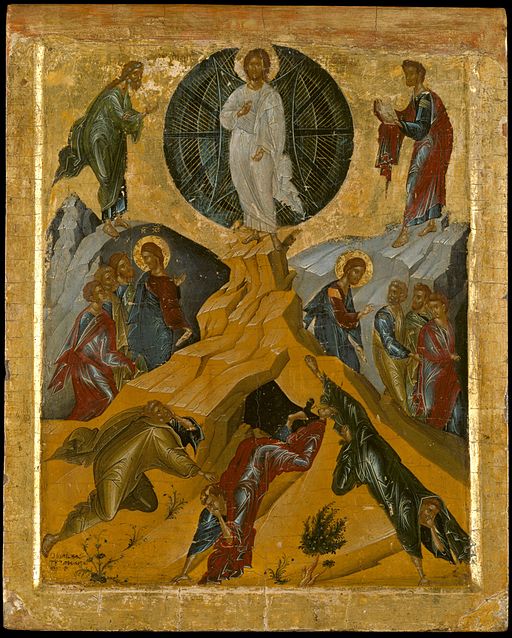

In the traditional icon the central figure is always shown with his face towards us, dazzled by the light.

In this 12th century icon from Mt Sinai, two figures are facing away from Christ, dazzled by the light:

In the following 15th century Russian icon the central figure is prostrated:

Book suggestions:

Books that I would start with for information on the iconography (ie symbolic content) of sacred art are a series published by the Getty Museum. They are not exhaustive, but are a good starting point:

Icons and Saints of the Orthodox Church for the canon of iconography.

Old Testament Figures in Art and Gospel Figures in Art and Saints in Art for western images that are not in the iconographic canon too. These books give a pretty thorough description of the meaning of the content of images they contain.

Occasionally use the different sorts of perspective that you get in iconography.

If you were to tour the churches of the various “Byzantine” or “Orthodox” denominations here in S. Florida, you find that popular understanding of tradition is nil. Some churches use Methodist realism, Others are heavily Romanies (Vatican I) like the garish common-book art in 1950 prayer cards. Several Uniate churches even have statues in the same 1950 silly style. The OCA recently build a large cathedral with swirling psychedelia images–kind of bad Chagall.

MY POINT IS that the American “orthodox: have nothing to teach RCs about icons (Obviously if one venerates ancient and medieval icons in Greece, Sicily, Italy, France, Romania, Turkey, etc. then the glories the Tradition permitted are apparent. But few American Orthodox have the interest or the money to do so.)

Since the Tradition is dead, why try to reinvent it?

Why not do what ancient and medieval oceanographers did. Hire professional artists, who are competent or, even (when possible) inspired artists, who also are convinced Christians. Pray, receive the sacraments, and use physical disciplines such as fasting and meditation to achieve purity of heart. Read the Gospels reverently over and over. Then paint what the Gospels say the best one can.

The results may not be as good as the best ancient and medieval icons, but it certainly will be vastly better than the icons in common use in the USA in 2016.

LikeLike