There is a scene from a TV sitcom I saw recently in which there was a scene in which a zombie movie was being made and the pedantic perfectionist director was permanently unhappy with his cast. In trying to get a more authentic performance out of his actors, he turned to one who had just completing a scene as a lowly extra doing nothing but the characteristically stiff, stuttering zombie walk: ‘Richard,’ he said, ‘Your performance – it’s good as far as it goes, but there’s still something missing. I’m getting lots of dead from you, plenty of dead, that’s great…But I’m not getting undead.’

This was a parody of whole genre of movies that seems to be here to stay and which seems to capitalize on the natural fascination of believers and unbelievers alike with our ultimate end and our desire for immortality. Aside from the classic zombie movies, there are others which seem to have similar themes – vampire films and werewolf films for example. Each will have some twist on the themes of either spiritual death and immortality; or spiritual death and bodily resurrection

I admit that while I am not scandalized by such things (perhaps I should be, I don’t know) I just find most of them pretty dull. I must be unusual in this respect for they are popular and most successful make a lot of money for those who make them.

There are some that over the years I have enjoyed. American Werewolf in London, for example, which is in part a comedic spoof. And there are other films that have similar themes and which are not horror films at all. Highlander, was sombre but not a horror film, for example. Groundhog Day is another in which the protagonist cannot die and regardless of what happens to him he rises again, spiritually dead but bodily resurrected – ‘undead’ in a manner of speaking. The relative optimism of Groundhog Day arises from the fact that it is made clear quite early on that a redemption of sorts is possible and in this imagined scenario the protagonist, played by Bill Murray, eventually breaks out the cycle of misery by becoming a virtuous, loving man. After countless failed attempts at getting the same day right, he finally succeeds by acting selflessly and is permitted, by the unidentified force that controls the rules of this make-believe world, to return to a familiar reality in which time moves forward.

Why are these films successful?

Prof Caleb Brown, whom I met recently is a screen-playwright and teaches a online film appreciation class called Christian Humanism in Modern Cinema told me that it is generally accepted that in the drama of film the highest stakes – what audiences fear most, generally speaking – is not death, but rather eternal damnation or eternal misery. This is, according to Hollywood, the audience’s greatest fear regardless, it seems, of whether or not they acknowledge the existence of an afterlife.

This is part of a simple, deeper answer, which is true of any drama. And that, strange as it may seem, is that these films speak in some way to our natural sense of the story of our own lives, which is as yet not fully realized. Any film will connect with an audience if at some level – albeit sometimes superficially or falsely – it seems to strike a chord in response to the basic questions of life – where do I come from? Where am going? And Why?

The Christian film, in common with every aspect of the culture, evangelizes by illuminating the fact that the story of our own lives is a participation in the grand drama of salvation. This may be done explicitly or subtly, directly or indirectly, but this is what it must do. Then it will stimulate the facility in us to recognize our true story in the Faith and lead us to it. There is even a place for the horror movie within this, I suggest, provided that they portray a message of hope. Regardless of the terror that is protrayed, real or imaginary, if it is portrayed as either redeemable or avoidable by means that is in some form that is analagous, at least, to God’s mercy then it will lead people in the right direction. Furthermore, because these are the fundamental questions that we all want answered, this is the film producers’ guide to greatest box office success, I suggest.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church tells (CCC282) that the bible tells us a story that relates to ‘the very foundations of human and Christian life’. And the story of the bible is told most effectively in the context of the liturgy as Fr Jean Danielou tell us in his influential book, the Bible and the Liturgy. I recently read Robert Taft’s book, The Liturgy of the Hours in East and West, and he makes a similar point. He tells us, p 371, that in order to profit from praying the liturgy as a whole, including the hours, as a school of prayer:

…one must e a person who prayes and whose life is penetrated with the Scriptures. The Bible is a story of God’s ceaseless calling, drawing, gathering and of his people’s constant waywardness. And the Fathers and monks of the early Church, in their meditation on this ever-repeated story, know that they were Abraham, they were Moses. They were called forth out of Egypt. They were given a covenant. The knew the wandering across the desert to the Promised Land was the pilgrimage of their life too. The several levels of Isreal, Christ, Church, us, are always there. And the themes of redemption, of exodus, of desert and faithful remnant and metaphors of the spiritual saga of our own lives.

And it is the first three chapters of Genesis are crucial to this story. They express in unique way the

‘truths of creation – its origin and its end in God, its order and its goodness, the vocation of man and finally the drama of sin and salvation’ (CCC 289)

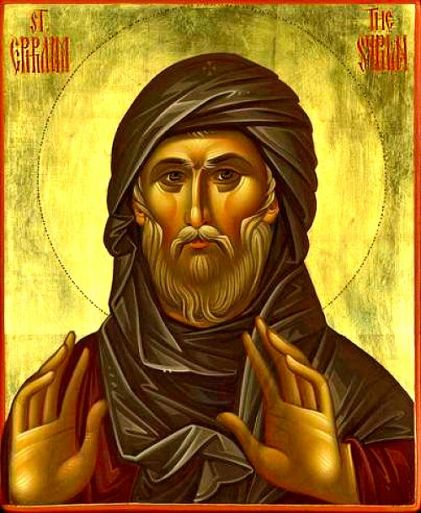

I recently heard of an interesting intepretation of the expulsion from Eden, as related in these early chapters of Genesis by Ephraim the Syrian, 3rd century Doctor of the Church.

He suggests it took place not as a punishment, but as an act of mercy to save mankind by preventing Adam and Eve from eating the fruit of the tree of life as fallen people. This would have condemned them, and us, permanently to an eternal life of misery without death, as fallen people.

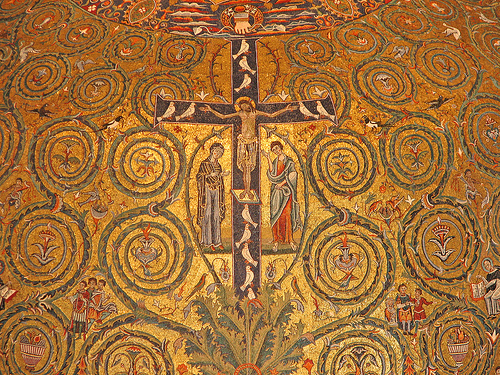

Rather than allow that to happen, the expulsion took place and then salvation was offered through the Christ and his Church. Through the triple sacrament of Baptism, Confirmation and Communion we die spiritually but then are raised up, again spiritually, and partake of the fruit of the new tree of life, which is Christ. This tells us that the possibility of an eternal but miserable life without death is not even possible – so we don’t need to fear vampires!

We can choose eternal misery after death, but through the mercy of God we never need to. This is the good news.

Just yesterday I read the following in the Office of Readings from St Cyril of Alexandria’s commentary on the gospel of John which relates to this:

When the life-giving Word of God dwelt in human flesh, he changed it into that good thing which is distinctively his, namely, life; and by being wholly united to the flesh in a way beyond our comprehension, he gave it the life-giving power which he has by his very nature. Therefore, the body of Christ gives life to those who receive it. Its presence in mortal men expels death and drives away corruption because it contains within itself in his entirety the Word who totally abolishes corruption.

I don’t mind a portrayal of flesh eating zombies or blood sucking vampires provided that they direct us to the flesh and blood that will genuinely give us eternal life. This is story that is worth telling and it is one that everyone wants to hear. We just have to tell it and maybe the horror genre is one way to do it.